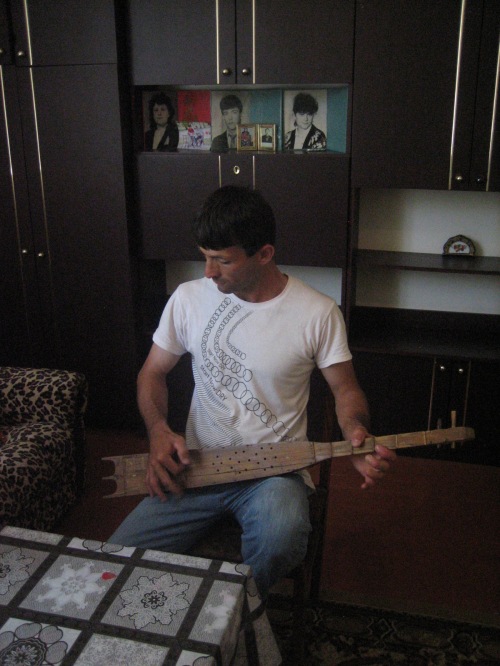

This past summer (2014), members of the Sayat Nova Project returned to Zemo Alvani to conduct recording sessions with Tush and Batsbi musicians and to distribute records and profits from “Mountains of Tongues: Musical Dialects of the Caucasus” to musicians. Below is an interview with Abram Baskhajauri, one of the three Tushetian chianuri players the Sayat Nova Project has recorded in Zemo Alvani. The interview, video, and photos of Abram are from July, during our third visit there. Special thanks to Dominik Cagara for his invaluable work as the Sayat Nova Project’s translator and Rezo Orbetishvili and his family for housing us, feeding us, and insisting that we drink what many would consider an excessive amount of wine.

SNP: How did you learn to play music?

AB: I was 15 the first time I went to Shirvan, Azerbaijan, with my sheep. My relative, who came with me, played chianuri. When the rest of the shepards went out, I went inside and tried to play chianuri. There was one older man who was with us and he discovered I was trying to play and he started a fight with me- “Why are you doing this? Who told you you could touch it?” The owner of the chianuri came in a bit later and told him “Why are you causing problems? This guy is young, he should learn if he wants to.” From then on the owner allowed me to play it – because I was his relative, he was supportive. At some point later we went to the mountains and made a new instrument and then I would watch my relative play and try to copy his playing.

SNP: How did you make a new instrument?

AB: We used sheep skin. People used to ask me if I had some kind of formal education but I haven’t. I’ve forgotten a lot – I used to know about 20 melodies.

[in this video Abram is telling a story about when he was studying tractor combine and having music classes at the same school. It turned out there were many melodies he knew that the teachers didn’t so at some point they would even start to dance together. The director came and said “what is this: music or dance class?” and the teachers said “He knows so many melodies we started a party here.”]

SNP: That’s great- so, this instrument is yours or your relatives?

AB: I made it myself.

SNP: Have you seen Gia’s chianuri?

AB: Yes, earlier, in the mountains, they made chianuri like mine, the round ones. Chianuris like Gia’s came later.

SNP: Did you have a model in mind when you made yours? Like your relatives?

AB: Yes, I saw some instruments in Azerbaijan and they were my inspiration, but they had strings made of horse hair. I use horse hair in my bow – this horse hair is from a Russian horse [laughs].

SNP: Why do you use metal strings? I know that in Svaneti they use gut strings for their bowed instruments.

AB: We used to make metal strings out of military surplus materials. In older times we used gut strings.

SNP: What happened when you got older? Where did you play? Festivals, parties?

AB: No, no, I didn’t take part in any festivals. I just played for people at home, for entertainment. This is our tradition – we have music at home. Someone comes, we drink, and we play.

SNP: Yes, we’ve been experiencing that. How did you learn new songs?

AB: You have to learn these melodies by heart. Once you memorize a motive, then you can use it freely.

SNP: Do you ever sing and play?

AB: No, I don’t sing. I have never seen a chianuri player sing and play.

SNP: Have you ever had any students, even in an informal context?

AB: No, no, no one ever came to me. I wouldn’t say no, because I don’t want this instrument to be lost, but no one came. I would like someone to learn it.

SNP: So are you worried about this tradition being lost?

AB: This tradition will be lost because no one is playing. Only Gia plays… and maybe Nikolas’ son.

SNP: So that means we’ve recorded all the chianuri players in Zemo Alvani?

AB: I don’t know, no one seems interested.

SNP: In what situations do you play nowadays?

AB: There was recently a concert in Kvemo Alvani and I was invited. I’m Jehovah’s Witness and a group of us are going to Lechkhuri forest tomorrow and I’ll play there. There was a long period when my wife was ill and I wasn’t playing at all. And then she died, and my son died, who was only 37, and I became very sad but started to play again.

SNP: I’m happy you are playing again.

AB: I’ve already lost a lot of melodies. I’m 84 years old so.. how long do I have left?

SNP: Thank you so much for talking with us

AB: Whenever you want, whenever you want, you know where I am, come and visit me.

There is a good possibility we will be taking Abram up on his offer. Members of the Sayat Nova Project will be returning to Zemo Alvani in order to make recordings at the annual Zezvaoba festival at the end of May. Here is some footage of the festival, recorded by The Sayat Nova Project in May of 2013.

![1175089_201954636643090_392633758_n[1]](https://caucascapades.files.wordpress.com/2013/09/1175089_201954636643090_392633758_n1.jpg?w=500&h=500)